|

So you know your ancient myths do you?

Are you sure? Really sure? Read on and find out. |

THE LABYRINTH OF CRETE

“I sing the tragedy of Theseus, son of Aegeus, who is called the Pride of Athens,” cried the storyteller.

A silver haired old man limped into the agora, the town square, announcing his story to attract custom and coins. He wore a long yellow and green tunic, the colors of a scholar. His cloak was gray and faded, the dark patterned border barely visible. Both garments were threadbare. Their age and disrepair told a story the crowd could read with ease. They knew their visitor for an easy mark, a philosopher fallen on hard times.

Clothes lie. Their stories are no more true than the men who tell them.

“Fie, old man. Why would we wish to hear such ancient stories? Why should we hear tales that glorify our foe, Athens?” The protester stood in contrast to the old man. Tall, young, and hearty, his sun darkened skin told of long hours laboring in the fields. His tunic was only one color, blue, but it was well cared for.

The old man’s disappointment showed on his face, but he’d known he faced an uphill battle when he arrived. Athens was far from popular in the Peloponnese.

An olive pit flew by the old man’s head, making a loud crack when it hit the stone paving behind him. More followed, thrown more for show than for malice. Some boys loitering nearby, given leave by a respected farmer’s heckling, decided to have some fun by expressing their distaste with the storyteller’s choice physically. The farmer raised no objection to the boys’ antics, though he resented losing his neighbors’ attention to them.

Violence was never far from away in the crowded cities. Though no one was seriously trying to hurt him yet, the old man knew the tide could turn in an instant. When a boy picked up a stone, he knew he had to gain control or flee.

“You only know the story as it is told in Athens, then?” His voice was clear and steady, belying his age and frailty. “If so, you have never heard the true story of Theseus. This story is held in secret that the shame of Athens is never known. And yet,” he paused dramatically.

Neither olives nor stones flew, though they were still held at the ready. “And yet I know the secret story, and I can tell it to you.”

“What is this secret, old man? What shame does Athens hide?” the heckler asked. The boys held their arms, waiting for his approval. The farmer was back in the lead, in control of the mob, and gloried in his position.

The storyteller raised his hand, palm outward, and lowered it slowly in a gesture for attention. “I offer the true story of Theseus, how he got through the labyrinth to fight the Minotaur, and the reason he rejected the kingship of Athens and gave birth to the demos of that city. Learn the truth. Learn that Theseus is not the hero he claims.” Another dramatic pause as he spread both arms out, palms up. “Would you hear more?”

All eyes turned towards the farmer, waiting on his decision as a proxy for their own. The heckler paused, torn between desires.

He tossed a coin to the old man, the head of Artemis the Hunter on one side of it. “Aye storyteller, I would hear more.” He’d made his decision.

Relieved, the storyteller took his seat, settling his tunic about him. While he sat down, others tossed him their coins and took their place in front of him. The old man winked at some boys who just a moment ago were throwing olive pits at him as they sneaked in to listen without the courtesy of a coin. He had coins enough today.

He hid his eyes behind his hands, then lowered them to view the crowd. He leaned forward seriously, and began his story.

θ

The ship was visible on the horizon when dawn broke over Athens. Both ranks of the bireme’s oars were out and its sail was up. It moved slowly but inexorably towards the harbor. The ship’s sail was black.

A woman wailed. The man next to her, her husband or brother, was shamed by her display. He escorted her away, his face fierce. Word spread from man to man, “The Black Ship is here.” The crowd dispersed, each man went to his home or at least away from the sight of the sea.

One man alone stood watching the Black Ship, his noble profile lit by Eos’ gentle beams. He was Theseus, Prince of Athens. Raised by his mother in Troezen, he had but recently come to his father’s city. He won the love of Athens by killing the Bull of Marathon and driving off the king’s consort Medea, and then by outwitting and killing the Pallantides when they tried to ambush him.

During his year in Athens he’d acted every inch the prince and the hero. He made a great effort to always show his best face. He did not know what the Black Ship meant to the city but he would not display either fear or ignorance. Instead he showed his bravery by putting on a stoic mein and standing solitary vigil as the ship sailed closer. Still clad in a short exercise robe for his morning run, he made a striking figure silhouetted against the dawn’s light.

The men of Athens saw his resolute stance. “How brave our prince, that he faces our shame so forthrightly,” some said. Others spoke of his valor, “See the fierceness in his eyes as he stares down the Black Ship. For our honor, he would renew the war on his own, were he able.” But this was Athens, where men would argue over where the Sun rises in the morning. So some said, “Observe this callous prince, who knows he will not be sacrificed for our shame. Instead he gloats as doom approaches.”

The noble prince took no notice of the crowd, but held his vigil in silence until the ship entered the harbor. Conscious always of his dignity, he left slowly and with his head upright so all could see there was no fear on his face. Theseus was cousin to Hercules, and determined to live up to the heroic burden placed upon him.

Before seeing his father, he had the palace slaves change him. Scrubbed down, oiled, and covered in a purple cloak, he sought audience with King Aegeus.

The king was in his private counsel chamber. Though it was called a private room, the king was not alone. Counselors, a few courtiers, and a larger number of servants surrounded him. Knowing the importance of his persona, Theseus spoke formally. “My king, I bear news from the harbor. The Black Ship has arrived and has caused much distress. I observed it enter the harbor, and can confirm it carries neither arms nor soldiers.”

The king stood, saying “It carries arms, my son. It carries the word of King Minos of Crete.” He walked his son to his private balcony, where none would overhear and they might speak in private. “King Minos’s son, Androgeus, died beneath the feet of a bull fifteen years ago at the Panathenic Games. Crete blamed us, launched its ships in fury and brought us to disgrace.”

In private with his father, Theseus let his mask slide. He stuttered “But, but, surely the ships of Athens…”

“Were as wind before Crete’s armada. The riches of Crete are no myth, Theseus, and they have a navy as strong as the world has ever seen. For the life of Androgeus, Athens itself was forfeit.”

“Yet we still stand,” the boy prince responded, finding his center again.

“Yet we still stand,” agreed his father. “But at a terrible price. For their forbearance, we must make tribute every Great Year, to be carried on the Black Ship.”

The Great Year came every seven years. This would be the third time Athens must pay the tribute. “And what is the nature of this shameful tribute we must pay?”

King Aegeus was pleased at his son’s perspicacity. “Seven youths and seven maidens, the cream of Athens’ crop, must present themselves to King Minos at the Palace of Knossos in Crete. At his command, they will be fed to his labyrinth to be destroyed by the great beast, the minotaur.”

Even alone with his father Theseus would not admit to a lack of knowledge. He was more than a prince, he was a hero. His legend grew each day, and he would not detract from his glory by conceding ignorance.

He knew of Crete, naturally, and had heard of King Minos. Of the minotaur and the labyrinth he knew nothing. His mother had taught him to read as well as any in Athens, for that talent is well regarded in their city. Theseus called for scrolls and read late into the night.

He learned. The minotaur was the child of Queen Pasiphae, King Minos’s wife, and Zeus, the King of the Gods, who had taken the form of a majestic bull. King Minos should have waited until the child was born, and then killed his wife and exiled the boy. Instead, he had the legendary inventor Daedalus construct a labyrinth of unimaginable complexity. The minotaur, a magnificent man with the head of a bull, was trapped in it. King Minos would send his captives and enemies into the maze to be killed by the creature. None ever returned.

The next morning the youth of Athens assembled in the agora. King Aegeus spoke while his men prowled the crowd seeking the seven fairest men and girls of the city. “It is with great sadness I carry out this duty, the cost of which must fall upon your heads. From your number we shall send seven men and seven girls to Crete, there to -”

“Six men,” interrupted Theseus. “We shall send six men from their number father, for I shall be the seventh.”

“My son! Why?”

“For the honor of Athens. Let none say we do not send the very best among us.” Theseus’s calm, in contrast to his father’s loss of composure, endeared him to the city even more than his sacrifice alone. He was just what they wanted in a hero.

“No. That’s not,” stammered the King, shaken. “My son, you are too recently returned to us. Your heroism is beyond question. Do not do this.”

“I must do this. But I shall return,” he announced proudly, the morning sun lighting his brow, “for I do not intend to die away from Athens. I shall go to Crete as tribute, but I shall return a victor. I will descend into the Great Labyrinth, and there I will fight and defeat the minotaur.”

The crowd erupted as Theseus raised his arms in triumph. Even Hercules had never received such an ovation.

“I will return in triumph aboard the very ship that carries us to King Minos. To let all know my triumph, I will change the sails to white on my return.” The spirit of victory descended on him. Only the actual deed remained.

θ

An eager crowd watched the Black Ship sail into the harbor of Crete. Murmurs spread like wildfire when they caught sight of Theseus. A bright green cloak separated the black tunic of the tributes from the ebon darkness of his hair. His noble bearing was enhanced by his clothing and the deference the sailors showed him. He held his hand out to stop the approaching guards, “Hold. My fellow tributes will disembark first.”

The guards stopped before his commanding presence while the crowd whispered in surprise. They had gathered for a celebration, a reminder of their glorious victory over Athens. They came to witness their foe’s humiliation, not to see him order guards about. Already, a few admired this prisoner’s audacity. They wondered how their victim came to be more than a prisoner.

It had been a difficult journey from the day they left Athens. They were plagued by ill winds that turned to storms two days later. Tossed by the winds, a torrential wave blew the ship’s navigator overboard. Without an instant’s hesitation, Theseus dove into the churning seas and swam to the drowning man. With great strength and surety, he carried the man back to the ship. In gratitude for his rescue, the captain awarded Theseus a green mariner’s cloak to wear over the tribute’s black tunic. The storms broke just as he tied the cloak over his shoulder. The sailors considered it a sign and treated Theseus and the other tributes with respect for the rest of the journey.

The sailors became so fond of the prince that a day away from Crete, the captain pulled him aside, “You’ve been blessed by the sea, and I don’t want to see you torn apart by that beast. I can tell King Minos you were washed over during the storms and claimed by the Gods. You can join us as a sailor. The King will never know.”

“Never, Captain,” he replied fiercely. Mellowing only slightly he explained, “You and your crew have my thanks for treating us well and for the honor you have extended to me. Duty and glory propel me in the same direction, and I shall gainsay neither. To Athens I have pledged my life, and to Olympus I have pledged my deeds.”

The captain shook his head sadly. Glory was a siren’s call. For each hero who reached its port, a hundred were dashed on the rocky shores. For him, it was enough that he reached Crete.

So it was that the tributes, buoyed by Theseus’s example, stepped proudly off the ship. None matched his commanding presence, but neither did any show cowardice.

“Now, you will escort us to the king please. Step quickly, we’re in a hurry.” Theseus continued to command the guards. Taking orders from a prisoner angered the lead guard, and he might have struck the young prince save for the crowd.

Admiration had spread through the mob. They were not jeering, but cheering the tributes. Fearful the crowd might turn on them, the guards escorted the tributes with haste.

Basking in their admiration, Theseus looked for any opportunity to increase his standing further. The Gods provide for the prepared mind. A young boy, jostled by the shifting crowd, fell into their path. A junior guard ran to kick the child back into place. As soon as he lifted his foot, Theseus pushed him over, yelling “Hold.”

The guards raised their spears towards Theseus, who stood poised and unruffled. Even unarmed, he was more than equal to a single guard. He had no chance against seven. The dramatic gesture and the roar of the crowd was his only defense.

He placed the child on his shoulders. “This young boy merely wished the honor of seeing his King up close, didn’t you lad?” The boy nodded, and the crowd roared.

“Come along then, and meet him with us.” He lifted the child high over his head, so all the crowd could see him.

Amid the crowd’s cheers, Theseus resumed his march. The tributes were watching him closely and followed their prince’s lead as soon as he began moving. This left the guards in the rear, only realizing the procession was moving when it was already under way. To all appearances, Theseus approached King Minos as an envoy accompanied by an honor guard. The crowd ate it up, by now entirely on Athens’ side.

King Minos had been watching the display from the beginning and was badly out of sorts as his Athens’ sacrifices approached. As soon as they were at the base of his dais he shouted over the crowd, “Men of Crete, see the price any who oppose us must pay. This is the cream of the city of Athens, come here to be fed to the dread minotaur. So perish all my enemies.”

The crowd roared again. This time the fickle mob cheered their king.

Theseus examined his opponent. King Minos was bald with a startlingly large nose. His narrow eyes glared down cruelly on Theseus. In his favor, the king had a commanding voice, perfect bearing, and the build of a warrior. Behind him and to the right was his wife, Queen Pasiphae. Of an age with the King, she was a startling beauty, and Theseus could see why Zeus himself would once have seduced her. Her large sea green eyes alone would make her a treasure, but when combined with smooth black hair, ivory skin, and wide lips, she was a beauty for the ages. On the other side of the king was his daughter, Ariadne, every bit as lovely as her mother but with the fresh bloom of youth.

“Tell us your names,” the king commanded, “that all of Crete will know those who sacrifice themselves for the honor of Athens.” He was playing to the crowd now, giving orders so Theseus’s glory would reflect back on him.

Theseus stepped forward, but instead of addressing the king, he lowered the child off his shoulders. “That,” he said pointing, “is your king. You are a Cretan, and should respect him when you are introduced. Bow to him.”

The child bowed uncertainly while the crowd laughed.

“Now on with you,” Theseus chuckled, “You’ve met your King, and may remember that into your dotage.” Before Minos could issue another command, Theseus looked at him and announced, “I am Theseus, Prince of Athens and son of Poseidon, God of the Sea.”

The crowd gasped. The King choked. Princess Ariadne smiled glowingly at him.

“What say you?” Minos glowered. “You are a Prince of Athens but claim not the parentage of the King. How comes a God’s child to take the place of King Aegeus’s son?” Theseus knew he had hit a nerve. As he intended.

Theseus stood proud, the other tributes arrayed as attendants behind him. “My mother knew both King Aegeus and Poseidon the night I was conceived. Both claim me as their son, and I claim both as my father, and let none gainsay me. Through one I am Prince of Athens, and through the other I am part divine and cousin to Hercules himself.”

“I deny you,” Minos responded bitterly. “That you are a prince of Athens I grant, and therefore you are a son of Aegeus. That you have the blood of the sea within you I deny. Let us see the proof of your claim.”

The king stood suddenly. With a single gesture his guards grabbed Theseus. The king marched back to the docks with them in tow. Two guards held the prince, while two more kept their spears high. Theseus tried to maintain his dignity. The crowd cheered weakly, puzzled by this turn of events.

By the water, Minos removed a ring from his hand and threw it far into the sea.

“Throw him in. Should his head break the surface before that ring, kill him.”

Theseus grabbed a quick breath and made a large splash an instant later.

θ

The waters closed around him as he sank into the Crete’s harbor. His cloak tangled around his arms and he had to waste precious seconds stripping it off. With powerful strokes he propelled himself down to the floor of the harbor, hoping against all hope to find the king’s ring before he needed to breathe again.

He felt the sandy floor more than saw it. He could barely make out shapes in the dim light, but his hands reached a solid surface. He was cold, aching, and his lungs were on fire. If he had somehow grabbed the ring now, he didn’t think he could survive to reach the surface. For a moment, he felt despair. His story would end in failure. The name Theseus would not be remembered by even the meanest singers.

Surrendering at last, he released his breath.

A bubble of air drifted up in front of him and out of reach.

He waited to die.

He waited some more.

He didn’t die.

He heard soft and feminine laughter from somewhere behind him. A pale light illuminated the world without color. A woman floated effortlessly in the water. He’d never seen her or her like before, but knew what she was. She was a Nereid, a water nymph.

Long dark hair floated freely in the water surrounding her. Wide eyes stared at Theseus over a small nose and mouth; a beautiful, wondrous triangular face. She only wore a strophion, a band of cloth women normally wore beneath the tunic, without a tunic over it.

“Do not fear, little cousin.” Her melodic voice sounded in his ears. “I will not let you drown. Not yet, at any rate.”

At last convinced he was not dying, Theseus took some time to right himself. He got his feet on the ground before responding. “You call me cousin, but I do not know you. I am -”

“Theseus. I know. And I am Thetis.”

“Thetis?” he asked, more than said.

“So I am.” Still floating a few feet above the ground, she bowed to Theseus. Her hair floated up away from her, exposing her magnificent bosom to him. A stray current pushed her forward, making the movement even more pronounced. Theseus was hard pushed to stay upright amid this vision of grace and beauty.

Thetis regarded him closely, and he thought he saw hunger in her eyes. The appetites of nymphs are well known, but so too are the dangers of approaching them unbidden. He took a deep breath to regain control and tried a neutral line of conversation, “Why do you call me cousin, beautiful Thetis?”

“My father is brother to your grandfather,” she answered. It was bad luck to speak the name of a Titan, though Theseus had not realized that applied to a Goddess too. “Did you not believe your own claim that Poseidon is your father?”

“Of course I do,” he protested. Thetis was laughing at him, he noticed as he prepared to launch a defense of his heritage. She playfully darted over and around him, dancing on currents he could barely feel. His best efforts to take control were failing, so he decided to change his tack and be direct. “Gentle cousin, I fear I must ask a favor of you.”

She laughed gently, “Of course you must. You are seeking the ring Minos threw into the harbor. Go ahead and look. I will not let you drown while I am here.” Her voice grew hard, “If you want more from me, you must pay my price.” She gazed at him, breathing heavily.

The colorless undersea world was strange to him. A stone anchor cut long ago lay half buried to his side, beyond which was a sunken coracle. To his other side drifted a torn sail, slowly sailing below the surface of the harbor, pushed now by currents instead of wind. The detritus of Crete was scattered through the harbor floor, among the crabs and clams.

It was difficult to even move, let alone search. His feet sank into the mire when he tried to walk. Swimming was easier, but he couldn’t look for the ring at the same time. While he struggled, Thetis swam nearby, laughing and watching him.

“Most lovely Thetis,” Theseus decided to take a chance, “it would surely take me a long time to search the harbor, and that would keep you occupied for far too long. Were you to seek the ring instead, we might find more pleasurable ways to fill our time.” He reached for her, but she darted away from him with disgust on her face. For a moment he feared her protection would fade.

She never vanished from sight and soon she drifted back to him. Theseus tried but failed to read her face, so conflicted was she. “Thank you for not deserting me to the water’s tender mercies, great Thetis,” he said to recover favor in her eyes. “You spoke of a price for your help, what may I pay?” He’d hoped to avoid paying a price through seduction, but paying was better than losing her help.

She smiled sadly. “Oh Theseus, do you give up so quickly? You had the price right, but surely you know to flatter a woman first.” As she drifted past him she let her hand brush his chest. Her words were playful, and Theseus was tempted to rush to her arms. The bitterness in her voice gave him pause. He worried that he was missing something.

There is no room for doubt when manipulating a Goddess, so he continued despite himself. “A goddess as lovely as you must be beyond petty flattery. How can words do justice to a face that rivals the Sun and eyes that outshine pearls? None can compare to your perfection from tress to toe.”

“Enough,” she commanded sharply. Her face softened as she drifted into Theseus’s arms. Yet she stood still and unresponsive as Theseus wrapped his arm around her waist.

“I am blessed beyond measure to hold so wondrously beautiful a woman,” he whispered to her. He did not understand her, but he could not stop now. His lips met hers as his hands caressed her back. Together, they floated off the harbor floor, wafting gently with the tide. Thetis became an aggressive lover in an instant, wrapping her legs tightly about his waist as she ripped his tunic off him and let it drift abandoned beneath the waves.

Nothing in his life had prepared him to make love to a Goddess, and doing so underwater was even further outside his experience. He learned quickly, and the lessons were pleasant ones. He lost track of time, lost track of position, lost track of everything save the eyes of a goddess and the soft quivering mass of her body.

“At last, dear Theseus,” she said after he’d given more than he had thought himself capable, “at last we are where we need to be.”

She pulled away from him and allowed her feet to rest near the harbor floor. She pulled her strophion out of the water and dressed in front of him. “You will prefer this to black,” she said as a long tunic drifted into her waiting hand. In the dim undersea light, Theseus couldn’t tell the colors. He clumsily draped it over himself and tied it off over his shoulder.

“Here is what you sought, and here is what you did not,” she said handing him the ring Minos threw into the waters, followed by a crown.

“What is this?” he asked with a broad smile.

She had an unsettled look on her face, but answered “You were better than I’d expected, and you deserve a reward. You must do more than just pass the king’s test, you must excel. This will be your triumph, and ultimately King Minos’s downfall.”

“I give you my thanks, Thetis. With your help, this was a far more pleasant task than I’d dared hope.” He was puzzled by the goddess’s concern for his glory, but accepted it gladly.

“Your task is not finished Theseus. We might yet see each other again.” He wasn’t sure, but thought she was sad when she said that.

He bowed as best he was able, but lacked the grace of the water nymph. Tucking the crown into a fold of his tunic, he took a deep breath and swam powerfully upwards. As he approached the surface, he made sure the ring broke the surface before his head.

A cheer arose from the few people still waiting for him. They gasped when Theseus, clad now in royal red and yellow, emerged from the water.

“We shall take you to the King,” announced the lead guard, the only one to maintain his stoicism. Theseus approved. He held his head high as he marched through the streets, showing Minos’s ring to any who watched. The crown he kept hidden.

“It seems you have passed our test,” King Minos announced sourly on Theseus’s arrival. “We recognize the parentage of both King Aegeus and Poseidon. My ring, if you please.”

Theseus handed it to the king, “Your ring, King Minos, was not the only thing I found in the harbor. Half of Crete has been abandoned there, it seems. Among the detritus I found this.” He held out the crown.

All eyes focused on him. No one spoke. Minos himself was stunned, his mask slipped for an instant before he stood. “This is my grandfather’s crown, lost these many years. Alas for Athens that they will lose such a prince. I would you had sent eight men, that I could spare one. In honor of this great gift, I grant you and the other Athenians freedom of the palace for this night. Until dawn breaks, you shall be our honored guests, save only that you may not leave.”

Theseus bowed, while the court looked on. None stared more hungrily than the king’s daughter, Ariadne.

θ

Theseus sank deep into his bath in the Palace of Knossos. Steam filled the room. He listened while the other tributes spoke excitedly about the events of the day. Hearing his exploits retold was almost as pleasurable as getting all the salt and dirt off of him.

Fetching young servant girls brought them grapes, olives, and wine while they bathed. Theseus was unaccustomed to this level of luxury. He’d been raised by his mother in Troezen, a far smaller city than Athens. Even noble Athens did not treat its princes as fine as Crete. He wished he could sample more of their wines, but feared the consequences when he descended to the labyrinth the next morning. This day had ended far better than it began, and he would make that true tomorrow also.

The king ordered a feast for the tributes, and provided them fresh clothing. To Theseus he gave a tunic in the same colors as the one Thetis gave him. While it bore the royal pattern of Crete, he also provided a gold badge of Athens. Theseus looked royal wearing it.

They ate goat from a spit and lamb stuffed with greens and dripping with oil. Servants carried plated of hummus, breads, and grape leaves. Grapes and winter oranges were available in abundance. With every dish there was wine. The tributes ate and drank as they’d never done before in their lives. Theseus sampled each dish but did not indulge. He accepted their admiration instead, and drank deeply of that.

King Minos left as soon as the feast started, to give Theseus pride of place. Queen Pasiphae and Ariadne came later to give them their blessings. “More than ever before, I wish we could spare the people of Athens this most dreadful tribute. Rest assured that we accept your sacrifice with heavy hearts and deep sadness. You shall all be missed.” While the queen spoke, Ariadne gazed unwaveringly at the prince in their midst.

When the meal was over, Theseus retired to a private suite the King had provided him. The evening’s surprises were not yet complete. The King’s daughter, Princess Ariadne, was waiting for him.

“Oh Theseus, Prince of Athens,” she cried when he entered, “all my life I have burned to meet a man such as you. I could not bear to lose you so soon. Spare me a broken heart; flee with me this night and let us run far from my father’s house.”

Copper and gold jewelry jingled when she rose to meet him. Her face was painted with chalk and mulberries, and her hair elaborately curled. Her bright eyes shone softly. She lacked the unearthly beauty of the goddess Thetis, but possessed her mother’s loveliness made fresh with youth. She trembled enticingly in his presence.

More worried about the maze than he let on, Theseus saw opportunity in her presence. He pushed her back, but kept his hands on her shoulders. Rejecting her, yet holding out hope with his touch, he told her “I can never flee from my duty to Athens. I will not die, but win eternal glory by defeating your champion and escaping the labyrinth.”

She fell to her knees before him and wept. “It cannot be done. Hundreds have been fed to the minotaur. None have returned. Oh please, good prince, flee the city with me as your prize. Surely that will be glory enough.”

Briefly discomfited that she showed no surprise at his plan, he rationalized that the king expected him to fight. He must have told his daughter. Theseus put his hand on her head, to keep her hopes high. “Even for one as lovely as you I cannot forsake both glory and duty. Surely you have gleaned some knowledge of the beast in your father’s court. With your help I may escape the maze, and then -”

“And then you would take me with you when you go back to Athens?” she pleaded at his feet. She gazed up at him worshipfully.

“You are your father’s daughter,” he said carefully, leaning down to cup her chin. “You are of Crete, and would not be made welcome in Athens.”

He made himself appear to be thinking carefully. “And yet, I might be able to convince my father to accept you, were I able to show him that your love is real.” With a simple promise, by giving his word, he might gain the edge he needed. He could always throw the girl over later, comely though she was.

“Oh it is, my prince, it is.” For an instant Theseus could have sworn he saw cunning in her eyes, like she was reading his mind. He put his guard up and watched her closely. “Let me wash your feet, please. I shall be your attendant, your father must accept that.”

She sat him down and personally fetched a basin. Then she unlaced Theseus’s sandals and bathed his feet with water and oil. She always looked at him adoringly, looked right in his eyes.

His loins stirred, but he restrained himself. He needed more than adoration from her. He needed a secret.

“Lovely Ariadne, you have touched my heart. If I could do as I would I should take you with me and make you my bride. Alas, I know my father and my city would both reject you. I must show them you will support me with all your heart.”

She lowered her eyes shyly.

Sobbed.

“My prince, there is… There is a way.”

Theseus waited. He rested his hand on her arm.

“Daedalus made the labyrinth so complex that even he could not escape it. He feared my father would entomb him in it, so he built a key he could use if needed. When he left Crete, he gave it to the keeping of a serving girl he cared for. She was my nurse as a girl, and she gave it to me in turn, against the day my father might turn against me.”

She paused. Theseus waited.

“Now I give it to you, my prince.”

Theseus smiled thinly. Inside he cheered.

“What is this key, my lovely Ariadne?”

“This.” From a fold at her waist, she pulled a spool of thread.

“String?”

“From Daedalus. Normal string will not do. The maze will cut string, or break it, or pull it, or twist it. Not this. The guards won’t even take it from you, just laugh. Others have tried making trails, but this will work.”

“I thank you, Ariadne. I will take you with me when I leave in triumph.”

She kissed his feet as though she were the meanest serving wench.

“Oh thank you Prince Theseus.” She stopped and choked back a sob. “Daedalus left instructions to be followed as well.”

“Then speak on.”

“You must follow these in order. First, you must never cross or reverse your path. The thread will mark your trail, and you must never step over it. Second, you must take two right turns followed by a left, and repeat that pattern except when it would make you cross your path. Finally, he said you must remember that there are many directions.”

“I see,” said Theseus as he memorized the words. “Hold on, what does that last part mean?”

“I don’t – I don’t know,” the lovely girl admitted. She looked away so Theseus could not see her face.

His work was complete, he had what he needed at the cost of a mere promise. He wanted to ravish the girl now, but he could not risk her father finding out about it and executing him before he entered the maze.

With some regret, he sent the young princess from his chambers, and retired to sleep.

θ

The Labyrinth of Crete.

He’d first heard of it the day the Black Ship sailed into Athens. Now only his skill and daring would stop him from spending the rest of his life there.

Fear gripped him. His stomach churned. The ground shook beneath his feet and the world darkened and blurred before his eyes.

No trace of it appeared on his face.

He stood tall and proud before the entrance.

The guards had their spears at the ready, but they looked on him with admiration. They had wagered on how many of the tributes would try to run. With Theseus in their lead, not a single one tried to flee. None of them hid their fear so well as the prince, but neither would they quake before him or their foes.

King Minos himself pulled the lever that opened the stone gate. It swung slowly inward with a small puff of dust. Minos said no words, gave no speeches. He raised a silent salute to the pride of Athens before the tributes entered, never to be seen again.

One at a time the tributes walked into the Labyrinth, Theseus last of all. Before crossing the border, he turned one last time. The guards raised their spears high, but Theseus returned the King’s salute, spun on his heel and entered the maze.

The gate closed.

Darkness fell.

But not entirely. Far above, small holes in the roof let in some light. It took time, but his eyes adjusted. High stone walls surrounded him, leading deeper into the maze.

To Theseus’s surprise, the labyrinth walls were not bare. They were covered with intricate frescoes and painted bright colors. He thought that would make it easier to navigate, but that did not fit Daedalus’s reputation. He looked more closely. The designs were cleverly arranged to fool the eye. A turn was concealed by the carvings; it blended in from one direction while being clearly visible from the other. They were landmarks, but ones designed to mislead.

“Gather round,” he yelled to the tributes. “I can travel through the labyrinth, and I will find and slay the minotaur.” He pulled the thread from the fold in his tunic. It glowed faintly; a helpful touch in the dark depths of the maze. “With this, I will be able to find my way back. I want all of you to wait here by the gate for me. Only come after me if the minotaur approaches. When we return to Athens, I want all of us to be there.” His triumph would be the greater for it.

“Yes my prince.” “All right, Theseus.” “As you say.” “I wanted to come with you.” Answers rang out from all the tributes. They would follow his commands.

There were no handles on this side of the gate, nor any other convenient handles on which to tie the thread. He felt foolish trying to tie it around a protrusion in a fresco, but it worked. Daedalus’s key held fast. Theseus unrolled the thread as he walked.

He passed the Attic Hills, the cliffs of Sparta, and the fleets of Crete, all carved into the walls with a master’s touch. A gap yawned to his right and he took it. A proud hoplite brandished his spear, and he passed the Attic Hills again. He hadn’t turned around, and the other tributes weren’t there. He tipped his head to the craftsman, Daedalus was a genius.

Passing a gap to his left, he continued until he could make another right. After that a left. The string trailed behind him. A right, and he noticed the corner was filed to a knife’s edge. Any other string would rub against it and be cut, but he trusted the master’s workmanship.

The light changed, sometimes stronger, sometimes weaker. If not for the weak glow of his thread he’d have crossed it in the dark when he almost made a left. Instead he kept going, until he could turn left later.

An hour into the march and he measured his life by right and left. He avoided crossing his path on many occasions.

And yet he made a mistake.

He could not turn right without crossing his path. Straight ahead was a dead end. He could not turn around lest he retrace his path.

He looked at the walls. The hoplite raised his spear again. He looked at the string, where he’d been, the paths he could not cross.

He saw another way

“No. That’s not a direction.” The words fell from his mouth without volition.

It was, and it was not. A direction he’d never known was there, found in a maze only one man could construct.

“Finally, he said you must remember that there are many directions.” Ariadne’s words echoed in his mind.

“You must remember that there are many directions.” This time it was a man’s voice, one he’d never heard before, but he knew it belonged to the inventor.

He went that way.

θ

The labyrinth was gone. Water surrounded him. The pressure hit him at the same time as the strain of moving in this new direction.

He gasped. Water rushed in to his mouth and lungs. Panic overwhelmed him and he thrashed about, tried to spit out the water he’d swallowed. Calmness, or maybe resignation, descended. In that stillness he realized he’d been breathing water for nearly a minute with no ill effect.

With a thought, he streaked through the water. Long flowing hair snapped in front of his face. Startled, he stopped in place. His hand was small, his arm long and slender. Looking down, large breasts rested on his chest. He wore a strophion, a woman’s undergarment, and nothing more. His body was no longer his own.

Shocked though he was to find himself a woman, he could not overlook his advantages. He could breathe the water and see through the darkness as easily as brightest day. Swimming was effortless and faster than he dreamed possible. He had too many questions, he needed more information.

There was a glint of light in the distance. In a flash he was off, darting through a school of fish, watching them scatter like birds around him. He was moving faster than a trireme at ramming speed and yet doing it almost lazily. The light he’d seen was a hoplite’s armor, the skeleton of the forgotten warrior still inside it.

With silent thanks to the unknown man, Theseus peered into the armor as a mirror. Looking back was an angular face with wide set eyes and a small nose and mouth. He was a Nereid. He was Thetis.

Daedalus was more than a craftsman, he was a genius. The path through the labyrinth led through the lives of others. Unless you found that path, the way that is no way, you would wander forever without reaching the center. All experience, all logic, all existence argued against that path, unless you are forced to find it. As the thread forced him.

Somehow he was also still in the labyrinth. If he concentrated he could see the walls surrounding him, with a glowing trail of thread still leading away. The walls moved with him, swimming did not move him through the maze. As soon as he stopped trying to see the walls they vanished. The sea was real, he could feel it surround him, taste the salt on his lips. And he could feel the void at his hips, his breasts on his chest. This was real; he was Thetis.

Theseus was a warrior, a scholar, and a philosopher. Yet, if he had to be a woman for a time, it were better to be a goddess, a mistress of the sea.

So he swam. He stopped periodically to see if he’d moved in the labyrinth, but he never did. His frustration would have overwhelmed him except that swimming was so much fun. When he moved fast enough to plaster his hair to his back and his breasts to his chest he could almost forget the unfortunate truth.

He heard a great splash and saw a man sink beneath the waves. The man struggled to pull off his cloak before swimming strongly down, still wearing a black tunic. Theseus knew who it was, knew him well. It was him. It was Theseus.

With a thought he extended his protection, commanding the sea not to harm his old self. As soon as he did, he felt something stir inside him. A desperate void opened in his legs, his breasts pulled tight. He felt a hunger such as he’d never before known. He remembered what happened when he met Thetis, and knew dread.

He started to flee. He could still see the walls of the labyrinth. He saw the thread trailing away, and knew that fleeing now would reverse his path.

He had a choice. He could see it clearly.

Run, and be lost in the labyrinth.

Or see it through.

“Do not fear, little cousin,” he said, hearing his voice for the very first time. “I will not let you drown. Not yet, at any rate.”

The bravest of men might quail before speaking those words. None of his deeds had prepared him for this. Fighting vicious Procrustes was a breeze in comparison to what lay ahead.

“You call me cousin,” he heard his old body say, struggling to keep his body upright in the shifting waters, “but I do not know you. I am -”

“Theseus,” he interrupted himself. “I know. And I am Thetis.”

“Thetis?”

The waters were cool, even cold, but he was burning with need. He wondered how Thetis, or any water nymph, could live with this constant yearning. He wanted to grab his old body and ravish it on the harbor floor. His pride restrained him. Despite his body’s urging, he did not want to be taken as a woman. Even more than that, he did not want to present himself badly. He was a woman now and must play the part properly.

“So I am,” he bowed. He feared this taking too long. Need could overcome him despite his resolve. Fear was another enemy, urging him to abandon his quest and flee. So he bowed with all the grace he could muster. The sea pushed his hair out of the way and his breasts outward toward his audience. His old body got a fine view, he remembered.

His male self did not try to take him yet, instead he made small talk about their relations. The whole time he burned for his old body to get on with it. He tried to remember what he’d been thinking, why he wasted so much time. Then he tried to hide his disgust as he remembered where that led, what he’d have to do to reach the minotaur. He wished he could speed things up, while his need conquered his revulsion.

“Were you to seek the ring instead, we might find more pleasurable ways to fill our time,” the male Theseus said while reaching for him. It was just what he needed. His nymph body and his quest for glory commanded the same response.

He couldn’t do it. The look of lust on his old face revolted him. To give in was to be taken as a woman, no, to become a woman. As Thetis the waves obeyed his desires, and his thoughts whisked him away from his male body.

Realizing what he’d done, he looked for the labyrinth walls. He had not crossed his path, but he would unless he got back to his old body. Glory would not drive him, it was not enough. But glory alone had not brought him this far, he also carried duty. Thirteen men and girls waited for him in the labyrinth, plus fourteen more every Great Year. His city knew shame while the tribute lasted. Glory helped, he admitted to himself, but it was duty that carried him back.

“Thank you for not deserting me to the water’s tender mercies, great Thetis. You spoke of a price for your help. What may I pay?” The male Theseus started speaking as soon as he drifted back into sight. The sour look on his old face surprised him. He hadn’t realized he’d been so bitter over having to pay the nymph’s price.

He wouldn’t have to. “Oh Theseus, do you give up so quickly? You had the price right, but surely you know to flatter a woman first.” It hurt to call himself a woman, even to himself. Even if it were true. He, no she, was a woman, as her body so clearly insisted. She ran her hand softly across her old chest, feeling the heat between them.

“A goddess as lovely as you must be beyond petty flattery. How can words do justice to a face that rivals the Sun and eyes that outshine pearls? None can compare to your perfection from tress to toe.”

“Enough,” she commanded. She wavered again, almost ready to flee once more. Words she’d once thought fine fell like lead about her. She let herself drift close to him, certain he’d take advantage.

“I am blessed beyond measure to hold so wondrously beautiful a woman.” He stepped into her, and his lips pressed against her.

She wrapped her legs around him and ripped his tunic off as she let her need overwhelm her. She felt his hands caress her breasts and lost herself to passion. Narcissus would envy her, she thought briefly. So lost in the moment was she that she could not mark the moment when he entered her and she became a woman in truth. She took perverse pride in noting her skill as a lover, as her old body coaxed her to ever greater heights of passion. The waves carried them at the command of her ecstasies.

Finally satiated, she let them come to rest. “At last, dear Theseus, at last we are where we need to be.” She knew he would misunderstand her. She was where her path through the Labyrinth had taken her. She commanded the waves to bring her clothing, and another for Theseus.

“Here is what you sought, and here is what you did not,” she said, handing him the ring and the crown he needed. He thanked her, believing it was his skill as a lover that compelled her aid.

“Your task is not finished Theseus,” she warned. “We might yet see each other again.” She knew he would, but from the other side. Despite herself, she knew he would hear her regret at the cost this path had taken.

She watched her old body launch itself towards the surface. She was able, again, to move in that direction that is not a direction, and was no more.

θ

“And that is how Theseus, the Hero of Athens, dressed and was taken as a woman.” The storyteller stood to let his audience cheer. A few had wandered off and a few more had joined while he spoke, but most had stayed through the tale.

“The story’s not over,” complained the heckler, still speaking for the crowd. “He hasn’t killed the minotaur yet, or even seen it.”

A chorus of agreement met his complaint.

“Oh, I thought you wanted the story of Theseus’s shame. I thought you wanted to hear how the pride of Athens was brought low.” The old man wore mock surprise on his face. “Surely you don’t want to hear about the triumph of your foe?”

The crowd did not know how to react to this challenge. They disliked Athens and loved hearing its shameful secrets, but they were also Greek and loved to hear tales of heroism.

The heckler stood when his friends urged him on. “It’s not so much that we wish to hear of Theseus’s triumph, old – storyteller. Better to say that we want to hear the full story. We paid for it, after all.”

“Well said,” “Yes,” “Tell us the whole story.” The crowd liked this reasoning.

The old man screwed up his face in sour thought. “I don’t know,” he hemmed, “I took payment to tell the story of Theseus’s shame.” A long pause, “But the fee you paid was far more than that story alone justifies. Your generosity is limitless.”

That got approval. His audience appreciated the flattery and the chance to hear more.

“It is also gratifying for a poor storyteller to speak before such an attentive audience.” He gave more flattery, and got more appreciation from the crowd.

“But story telling is thirsty work. Perhaps some beer would allow a poor teller of tales to salvage his dignity and claim he did not tell a new story for free?” Hearty approval mingled with laughter through the agora.

The heckler, pleased the tale would continue, offered to bring a barrel for the crowd.

“Most generous. But since we will be pausing to wait for our benefactor,” he nodded politely, “I fear a spirit of hunger will haunt us and distract from my poor tales.”

A few nods, but tentative ones, met this pronouncement. They weren’t sure where he was going.

“We could continue the story tomorrow,” the old man sad with exaggerated sadness. “It would be a pity to wait. You may not know the end of the tale so well as you think. Theseus shall know more shame before he knows triumph. And his final triumph is not at all what he expects. Still,” he said with a sigh, “there would be no harm in holding the story until the Sun rises again.”

“A goat, bring in a goat,” shouted a shepherd who’d been listening to the whole tale. “I’ll be back in the fields tomorrow, and be damned if I miss the end of the story.”

“Stay here storyteller,” shouted a boy as he ran off.

The crowd broke apart quickly, each man running to get something for the impromptu feast. A few stayed to make sure the old man did not stray.

He didn’t. Beer, a meal, and coins. There was little more a teller of tales could ask for.

The story itself? That could wait until after he ate.

Comments

very different take on the legend

very neat one, liked it a lot.

New Twist to old story

and yet you kept the true to the original. Nicely done!

Hugs

From Grover a lover of the old myths!

Which just shows

As long as there have been story tellers, there have also been cliffhangers!

/hugs

The Shame of Theseus? Why not

also the triumph of Thetis? There is so much to be told of this meeting. And according to the movie Clash Of The Titans, Thetis has a son

May Your Light Forever Shine

Her son is Achilles

That's entirely correct. Thetis's son is Achilles, by Peleus. It's not always simple to unwind the chronology of Greek Myths - oddly, consistency didn't seem to be high on their lists... However, you can put a few things together. Theseus and the Minotaur had to happen before Paris kidnapped Helen of Troy. So we're still 5-10 years out from the Trojan War. Of course, Achilles wasn't just born then. I'm taking the view here that Thetis has not yet married Peleus, since she was another very loyal wife. She operated under a prophecy, by the way, that her son would be greater than the father - which in the stories of the time usually meant he'd overthrow his father, as Zeus did to Chronos. So you could easily see malign motives in Poseidon sending her after Theseus here. Anyway, that's just me going into more detail than is really needed.

Glad you liked it, anyway.

Titania

Lord, what fools these mortals be!

Thans!

I always forget if he was Thetis' or Metis' (Metis' first was Athena, I think) child...

Or was that Themis? I'm so confused

Your story teller

Is canny, as should be but I loved how you described the way he got the crowd into his story. 'The shame of Athens' has a lure that even draws a person now. It's clear that you've read the myths because your narrative, cadence, and dialogue were very close to how those were told.

Now. As Paul Harvy used to say... "The rest of the story."

Maggie

That...

...was excellent!

Very good

We all know that the end of Ariadne was not nice though, I hope it changes this time around.

Ariadne was always interesting

Once I started studying them in more depth, it was the imports that fascinated me more than the natives, as it were. Ariadne was probably a Cretan deity before she was incorporated into the mainland's mythologies, and you can see it in some of the variations in the tales about her that remained even when most of the rest of the mythology was more settled. I made some choices as to which parts of her story to encompass in this version, and they'll show up mostly in the second part. Sorry if that sounds vague, but just in case some people don't know the ending of the story by heart, I don't want to spoil it.

Hope you're happy with it, and thanks for the comments.

Titania

Lord, what fools these mortals be!

Perfect

A silver haired old man limped into the agora, the town square, announcing his story to attract custom and coins. He wore a long yellow and green tunic, the colors of a scholar. His cloak was gray and faded, the dark patterned border barely visible. Both garments were threadbare. Their age and disrepair told a story the crowd could read with ease. They knew their visitor for an easy mark, a philosopher fallen on hard times.

Clothes lie. Their stories are no more true than the men who tell them.

This passage is just about perfect.

:D

What if, when Minos tossed his ring into the harbor, he had told Theseus to go fuck himself? = )

*GiggleGiggleGiggle* :D

The art of story telling.

Is alive and well. The oral traditions of relating a story goes back to the dawn of human ability to speak to one another. Your story captured the spirit and wit of how the foke tradition morphed a classic story into something just a bit different to save his neck. Good read of his audience, and a great save from physical harm. This also illustrates why so many different versions of stories comes down to us.

With those with open eyes the world reads like a book

Halfway To Paradise

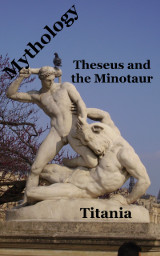

I've always had a soft spot for ancient Crete. Images like this might give you an idea why.

Rose-tinted though this view no doubt is, I can't help feeling that on one little island around three and a half thousand years ago the human race came as close to paradise as it ever will.

And then Thera had to bloody erupt. Thanks, planet earth.